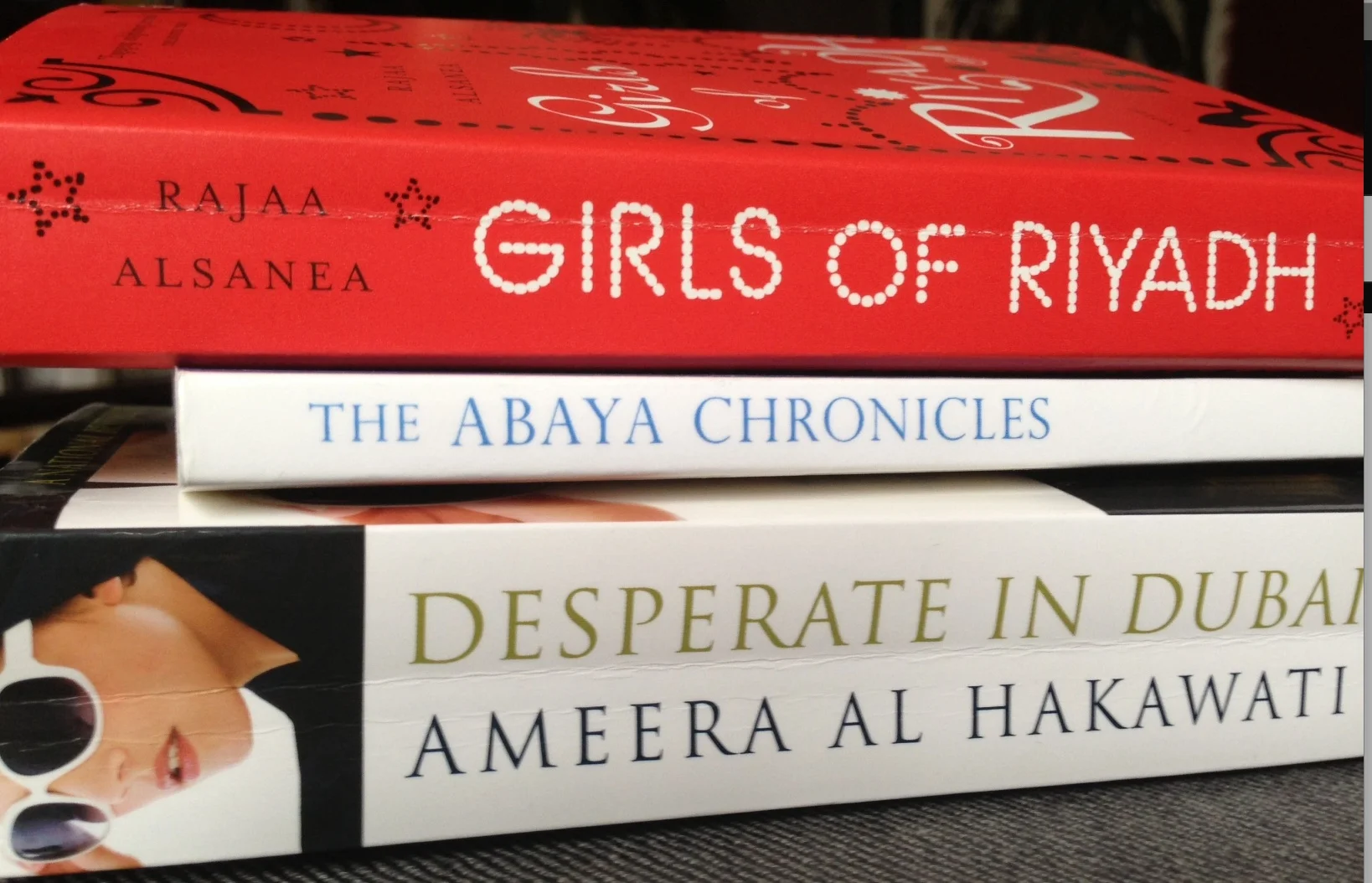

Guilty pleasure: tales from behind the veil

As a visit to any bookshop in the UAE

reveals, an entire genre of novels based on the promise of

‘lifting the veil’ and revealing the ‘hidden lives’ of women in traditional Muslim

societies has emerged and is doing brisk trade. Many of them, such as Jean Sasson's blockbuster Princess series, deal specifically with the lives of women in Saudi Arabia. Slowly but surely, the women of the UAE are also becoming the subject of such literary portrayals.

To me, these books are strangely irresistible,

a guilty pleasure. Guilty, because the reasons for this

fascination oscillate between a principled intention to explore local writing and an indignant kind of voyeurism. Awkward stuff. But I can't help myself, I want to read them all. For better or worse, these are the three tales from behind-the-veil I've devoured most recently.

I find myself picking up these books indiscriminately; even the ones

I know I will hate, like the supremely trashy Desperate in Dubai. The reason this kind of literature can be both so appealing and so infuriating is because it plays with the boundary between the real

and the imagined. Like so many others, the three novels mentioned here are based on/inspired by real events and, while they don’t have much else in common with Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, they also leave fact and fiction tantalisingly, and at times problematically, entangled in the

reader’s mind. Considering the strict religious and cultural codes of the Arab Gulf, this ambiguity is risky, but profitable business.

What strikes me is that, because of the social norms involved, the authors' choice to write fiction, rather than straight-out non-fiction, gives them the fabulous opportunity to have their cake, and eat it, too. On the one hand, when faced with moral outrage from conservatives, they can say, 'Well, it's just a novel!'. On the other, their work is automatically taken more seriously because people know about the strict rules it is bending. Good on them.

Another thing the novels share is a self-conscious concern with the way women of the Arab Gulf region are imagined by outsiders as well as compatriots. What is the ideal? What is the price for deviating from it? Some expositions on different 'types of women' and what happens to them, can seem moralistic, but, overall, an image of the women of this region emerges that transfigures the tragic/traditional (depending on where you're standing on this) figure of the silent, virginal, veiled woman in black into something altogether different: stronger, funnier, more in control.

The basic narrative structure is also the same. At the centre of each novel is a group of women, whose lives intersect through friendship, work or family, and whose different personalities and backstories represent some of the 'typical' female figures in society: the rebellious heiress; the likable dimwit; the entrepreneurial youngster; the quiet religious one. In their own ways, all three books both shake up and utilise such cliched notions. Here they are, in descending order of appreciation.

The oldest and most successful of them, The Girls of Riyadh, by Rajaa Al Sanea, was published back in 2005. In it, we follow the lives of a group of friends as seen through the eyes of the narrator, a determined Saudi student, who starts a mailing list to share stories of how the different personalities deal with the challenges of family, love and life. The complex and burdensome relationship between men and women in Saudi society are questioned and, although the book falls into the narrative genre of “rich people with problems”, it shows that, as a Saudi woman, no matter how affluent and educated, your happiness and wellbeing is always firmly in the hands of your male relatives. In 2006, Saudi courts rejected a case against Al Sanea on the basis of the book being “an outrage to the norms of Saudi society. It encourages vice and also portrays the Kingdom’s female community as women who do not cover their faces and who appear publicly in an immodest way.” Publicity such as this can’t be bought.

The Abaya Chronicles, by comparison, chooses a diplomatic, even motherly, approach. In 2010, Fulbright scholar Tina Lesher published a novel based on the rare and personal insights into Abu Dhabi’s female population she gained during two tenures at Zayed University. In describing the worries and aspirations of her conspicuously perky cast of Emirati students, entrepreneurs, housewives and OAPs, Lesher does touch on controversial issues such as mental health, but the overall tone is chirpy. The writer’s didactic instincts also make themselves felt, which can be a little tedious, but her accounts of the older generation of women and their experience of rapid modernisation are rare and well worth reading.

The tagline on the cover of Desperate in Dubai describes the novel as the ‘UAE’s answer to Desperate Housewives’, an answer authored by an anonymous Emirati writer under the pen name Ameera Al Hakawati. The book, already in its ninth edition, is probably going to continue doing well for some time, given the utter lack of competition and the scintillating mystery surrounding it. Unfortunately, I have little good to say about this particular reading experience. High-consumerist dream sequences and the use of brand names as a narrative device is not for me. In the book’s defense, there are plenty of risqué romps (it was even briefly banned), some actual suspense and at times even a glimmer of a girl-power message. But I found that I had to force myself to finish it, an achievement wrought by swallowing down all sorts of intellectual reflexes. Engaging and educational in the way of Jersey Shore.

A novel is a commercial work of fiction, which means that creative license and a desire to entertain are at work. If you are interested in learning more about the lives of women in the Muslim world, my advice would be to read these novels, among others, but for heaven’s sake don’t take them too seriously. Enjoy them for what they are, then get out and make up your own mind.

P. S.: I realise that this might be easier said than done. Because of the way society is set up, here and

elsewhere, there is limited opportunity for non-Muslims and/or non-Gulf Arabs,

especially men, to make their own observations. Interaction with local women usually happens at work, at official institutions or other formal settings. The allure of these novels, therefore, lies in their claim to make the unknowable known, notwithstanding the Orientalist gaze, patriarchal pride and sheer boneheadedness.